Some thoughts on macro-analysis

‘Distant reading’ and ‘macro-analysis’, while as terms not interchangeable, as concepts have their provenance in the early twentieth century, particularly in the work of Roberto Busa, who realised that to continue his research he needed ‘some type of machinery,’ (Busa, 1980 p1). Jockers contends that ‘a macro analytic study of several thousand texts might lead us to a better understanding of the individual texts’ (2011, p2), and his analogy to micro and macroeconomics is helpful in understanding the area. He argues in his work that macro-analysis should be used in conjunction with interpretative approaches to bring to light new information and detail not accessible through traditional methods. In critically analysing the work of researchers using such techniques, some common features emerge: Firstly, that digital ‘tools’ are just that – they are not an end in themselves. Researchers adapt or design computational tools and to modify data sets in order to respond to their own research questions (Lundy, 2020), (Ramsey, 2011), (Muralidharan and Hearst, 2013). Secondly, where tools can reveal information that supports existing knowledge, the most interesting results are to be found in the ‘textual moments where the numbers simply don’t add up.’ (Steger, 2013 p25). Finally, digital analysis works best when texts are compared – to each other or to a larger body of work. Hoover uses a simple example to illustrate this: concerning the contention that the poem ‘The Snowman’ contains a large number of nouns, he suggests that such a statement is meaningless without comparison, and that computational techniques are most useful ‘investigating textual differences and similarities’ (Hoover 2013, p1).

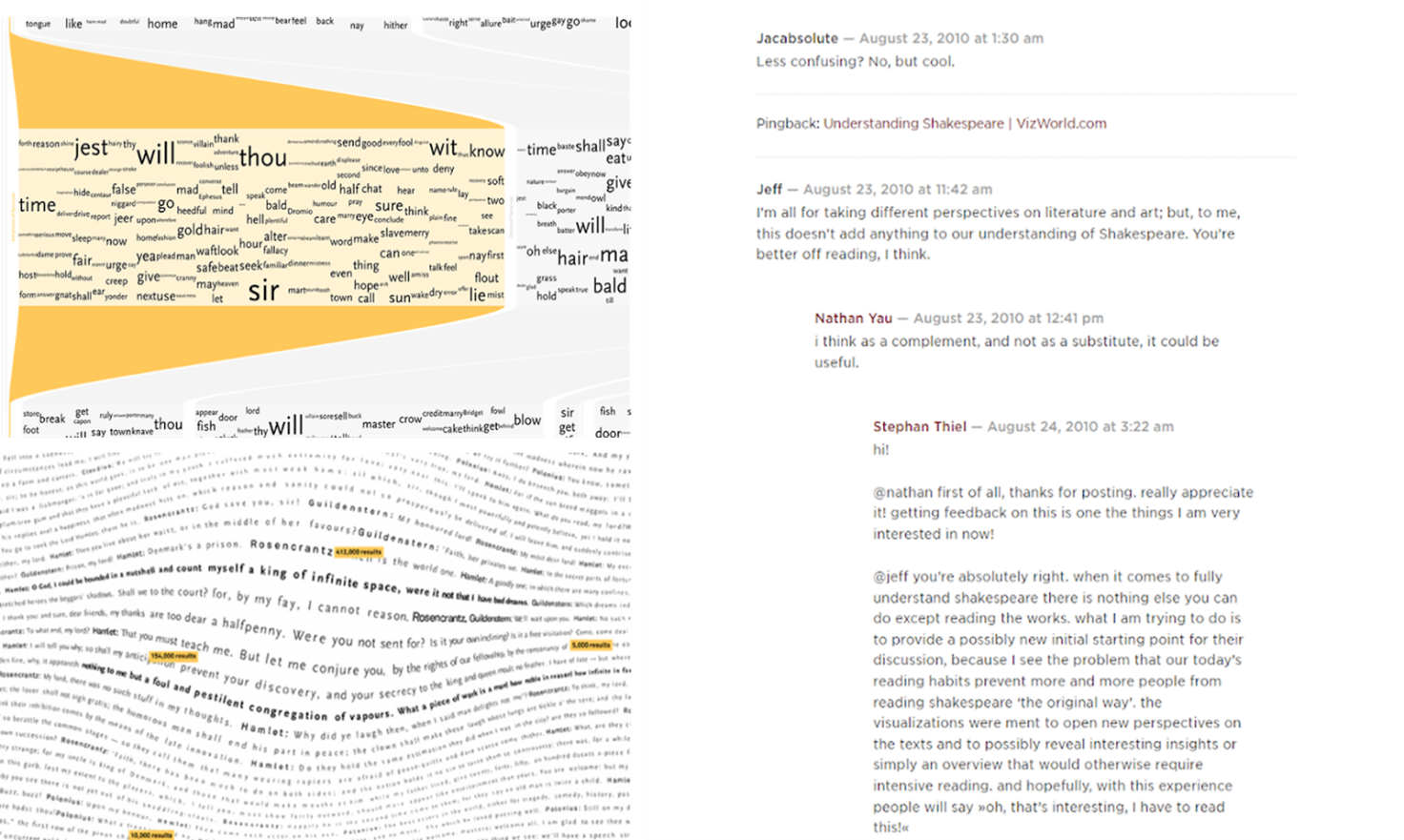

Initially, the application of digital tools to analyse texts appears limited in scope – what, after all, can a computer do except count? Research has demonstrated, however, that digital textual analysis can both add to existing scholarship and be innovative. In terms of literary analysis, large databases already in existence attract scholarly attention. Shakespeare’s corpus has been much examined. Recently Wilhelm et al., (2019) have contended that their tool – created to aid the visualisation and analysis of Shakespeare – adds to existing scholarship, but also has the potential to help interpretation in a classroom setting and has practical applications for directors planning stage productions. That such analyses can be of use outside the realm of academia, is important in raising the profile of the Digital Humanities as a discipline. Creative visualisations resulting from macro-analysis, whether for the purpose of scholarship or art, can also generate debate in the area. Consider Thiel (2009), who used his textual analysis to create visual representations, resulting in dialogue between viewers and the researcher online, demonstrating that the debate around whether such visualisations can add to scholarship or not does not have to be confined to academic circles.

While acknowledging that computers do in fact ‘count’ as opposed to interpret, it would be remiss to assume that computer-based techniques add nothing in terms of the consideration of style. Researchers have proven that function words are ‘not ‘empty’ but philosophically rich’ (Busa, 1980 p83). The examination of words traditionally regarded as ‘stop words’, when considered as part of a large corpus, form a trail of literary breadcrumbs leading back to the author (Jiménez, 2019), and ‘often contribute most to the “style” of a text’ (Steger 2013 p15). One real world application of the analysis of such words is described in Pennebaker (2011), which analysed 296 speeches, interviews, and articles, from known extremist groups, in terms of function words, aiming to assess the extent to which language could or could not be deemed a reliable predictor of future violent acts. It should be noted that as interesting as the study is, the author himself points to a limitation, cautioning that ‘Language use is a dynamic system that is constantly changing, making it an ever-shifting predictor of future behaviours’ (Pennebaker, 2011 p101). This reflects the view that macro-analysis is dependent on interpretation, insight, and the judgement of humans, and cannot therefore in itself represent absolute truth.

Further benefits of the application of digital tools seen in the process of network analysis, an area that combines the literary and sociological. So and Long’s 2013 study of modernist literary networks reveals broader sociological data about how networks can influence poetic form, and how poets’ work was influenced through their connections and the journals they wrote for. The study of networks and creative clustering becomes relevant too in research where stylometrics have been applied to determine authorship, for example the many studies in the ‘who wrote Shakespeare?’ debate. Networks, albeit on a smaller scale, feature in examining a familial sphere of influence in recent work on the authorship of Wuthering Heights. Given what Steger (2013) has referred to as Emily Bronte’s ‘masculine style’, McCarthy and O’Sullivan (2020), found that the results of their study concur with evidence that the Brontes, like other networks, were influenced by each other in a creative cluster. I find this of particular interest having undertaken a study as an undergraduate in the 90’s, which analysed, through close reading, the extent to which the poetry of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes formed a kind of poetic dialogue during the course of their relationship – an interesting topic to revisit using digital tools perhaps.

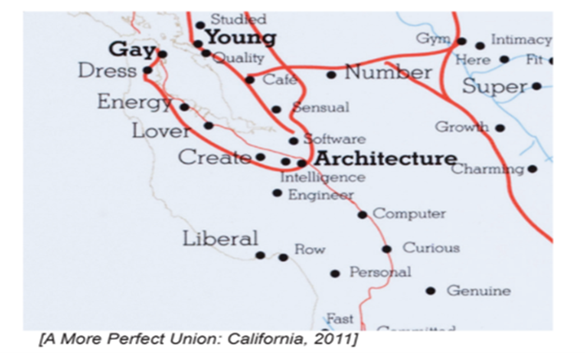

So and Long’ s work indicated that the uses of computational techniques in analysing texts can extend beyond the academic or the literary, and inform broader cultural and sociological research. Similarly, analyses of discussion posts, social media platforms, and social data, are valuable in that such information is culturally and socially situated and ‘reflect the ideas, values and beliefs of both their authors and their audiences.’ (Nguyen. et al., 2020 p2). Macro-analysis argues Jockers (2011), mitigates against the possibility of ‘cherry-picking of evidence.’(p22), thereby adding to accuracy overall. Furthermore, the most beneficial aspect of macro analytics is the discovery of ‘outliers’ in the data that are, in the end, the real objects of interest and further study. (Kirschenbaum,2007), (Correll and Gleicher 2012). These theories converge in the work of R Luke Dubois. His ‘A More Perfect Union Project’ (2011) renamed cities and districts in America using the word most unique to that area, as indicated in the profiles of dating apps. The choice of DuBois was to visualise the ‘outliers’ – not the most popular word in a city or area but a word unique to that place. The map represents a moment in history; is based on the meta-analysis of text gleaned from over 19 million users in twenty-five databases and resulted in what he called an ‘alternative census’, focusing on what people considered important in their lives. DuBois does admit that given his intention and how he used the tool, what was produced was ‘not an absolute truth simply because it’s based on statistics.’ (Goodyear, 2017), proving once again the centrality of the researcher in the process.

Some of the limitations associated with computational analysis have been described above: the contention that computers merely parse text; the changing nature of language and interpretation; the question of how and whether evidence gathered and represented in this way will be universally accepted; but others exist too: the issue of whether research question and digital tool are compatible; that lengthy work may be completed for relatively little reward; and the impact of ill-prepared data sets. Critics are doubtful overall of the singular trust placed by researchers in the value of computational analysis to the exclusion of traditional methods – an example being the work of Craig and Kinney (2009), in examining the authorship of Shakespeare. Both Jiménez (2019) and Hoover (2016), suggest that the decisions made by the researchers, and the tools used, have not added to scholarship in the area, having ‘reached the limit of linguistic analysis by computer’ (Jiménez, 2019 p11), and produced conclusions which fail to properly consider the dating of the plays, or Shakespeare’s sphere of influence accurately.

Hoover cautions that all texts and data sets require preparation. Dialect, spacing, apostrophes, hyphens and particularly spelling variations can all create issues in computers identifying tokens. Consider one example he provides: ‘He said, “That’s ’bout ‘nough, sho’.”/ “That’s ‘bout’, not ‘fight’; ’nough said,” Nough said’ (Hoover, 2015 p4). Clearly without significant intervention no computer could ‘read’ this with accuracy. Regarding Ramsey’s analysis of Virginia Woolf’s ‘The Waves’, Hoover (2016) questions the decision to attribute certain words to characters both when they used them and when they quoted them – arguing reasonably that the second instance does not illustrate the word as part of that character’s vocabulary. These points illustrate clearly that in computational analysis, two researchers, using the same texts and the same tools, could produce different results depending on how the data or the tool was prepared. O’Sullivan (2017) points to this in highlighting the centrality of the researcher and interpretation, in his critique of studies comparing language used by and about male and female writers, pointing to the need to address how data sets are prepared, to consider nuance, to avoid misinterpretation of data, and concluding that with increased use of machine-based analysis of literary texts, ‘the role of the human has never been more important.’

Other recent additions to scholarship in the area reap the benefit of hindsight and the lessons learnt from such critiques as described above. Lundy (2020) combines the literary with the sociological in his study of New York Times bestsellers. His conclusions acknowledge the need to employ a ‘mixed methods approach’ (Lundy, 2020 p19). Furthermore, in casting a critical eye over the limitations of his own research, he suggests that his findings do not exist as ‘perfect distillations of fictional trends’, rather they serve ‘to complement existing knowledge….and to raise questions’ (ibid, p59). As analytical tools have become more widespread, and researchers more adept at their design and application, their role in creating both possibilities and challenges is embraced, with caveats. The literature is clear that research in the arts is ‘a cycle of reading, interpretation, exploration and understanding’ (Muralidharan and Hearst, 2013), and that the role of technology in this is largely to bring to light information indiscernible through traditional methodologies (Nguyen, et al., 2020), for use alongside those methodologies. Through the use of computational techniques, as indicated in Kirschenbaum, (2007, p5) ‘Reading is not so much “at risk ” as in the process of being remade.’

Bibliography

Busa, R. (1980). The Annals of Humanities Computing: The Index Thomisticus. Computers and the Humanities, 14(2), 83–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30207304

Correll, M., & Gleicher, M. (2012, October). What Shakespeare taught us about text visualization. In IEEE Visualization Workshop Proceedings: The 2nd Workshop on Interactive Visual Text Analytics: Task-Driven Analysis of Social Media Content.

Craig, H. and Kinney, A.F. (2009) Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship. Cambridge University Press

Goodyear, Anne C.. (2017) ‘What You See Is What You Get: The Artifice of Insight: A Conversation between R. Luke DuBois and Anne Collins Goodyear’ Artl@s Bulletin 6, no. 3 : Article 8.

Guzzetta, G. (2014). Jockers, Matthew L. macro-analysis: Digital Methods and Literary History (University of Illinois Press, 2013). ISBN 9780252037528 (Hardcover), 9780252079078 (Paperback). Digital Studies/le Champ Numérique, 4(1)

Hoover, D.L. (2016) Argument, evidence, and the limits of digital literary studies, Debates in the Digital Humanities, pp. 230–50

Hoover David, L. (2015) ‘The Trials of Tokenization’, Global Digital Humanities Conference Hosted at Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia June 29, 2015 – July 3, 2015

Hoover, David, L. (2013) David L., “Textual Analysis” | Literary Studies in the Digital Age’ Available at: https://dlsanthology.mla.hcommons.org/textual-analysis/

Jiménez, R. (2019) ‘Shakespeare by the Numbers: What Stylometrics Can and Cannot Tell Us’ Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship. Available at: https://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/shakespeare-by-the-numbers-what-stylometrics-can-and-cannot-tell-us/

Jockers, M. (2011) ‘On Distant Reading and macro-analysis’. Available at: https://www.matthewjockers.net/2011/07/01/on-distant-reading-and-macro-analysis/

Kirschenbaum, M. (2007) ‘The remaking of reading: Data mining and the digital humanities’, … Foundation Symposium on Next Generation of … [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/35646247/The_remaking_of_reading_Data_mining_and_the_digital_humanities (Accessed: 21 February 2022).

Lundy, M. (2020) Text Mining Contemporary Popular Fiction: Natural Language Processing-Derived Themes Across over 1,000 New York Times Bestsellers and Genre Fiction Novels. PhD Thesis. University of South Carolina.

McCarthy, R. and O’Sullivan, J. (2020) ‘Who Wrote Wuthering Heights?’, Digital Scholarship In The Humanities, (9 pp)

Muralidharan, A. and Hearst, M.A. (2013) ‘Supporting exploratory text analysis in literature study’, Literary and Linguistic Computing, 28(2), pp. 283–295. doi:10.1093/llc/fqs044.

Nguyen, D. et al. (2020) ‘How we do things with words: Analyzing text as social and cultural data’, Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, p. 62.

O’Sullivan, James (2017) ‘Computing differences in language between male and female authors’, RTÉ Brainstorm, 19 October

Pennebaker, J.W. (2011) ‘Using computer analyses to identify language style and aggressive intent: The secret life of function words’, Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, 4(2), pp. 92–102. doi:10.1080/17467586.2011.627932.

Steger, S. (2013). Patterns of Sentimentality in Victorian Novels. Digital Studies/le Champ Numérique,

3(2). DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.235

So, R.J. and Long, H. (2013) ‘Network Analysis and the Sociology of Modernism’, boundary 2, 40(2), pp. 147–182. doi:10.1215/01903659-2151839.

Thiel, S. (2009). Understanding Shakespeare. Towards a Visual Form for Dramatic Language

and Texts. B.A. thesis. http://www.understandingshakespeare.com Underwood, T. (2016). Distant reading and recent intellectual history. Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, 530-533.

‘Seven ways humanists are using computers to understand text.’ (2015) The Stone and the Shell, 4 June. Available at: https://tedunderwood.com/2015/06/04/seven-ways-humanists-are-using-computers-to-understand-text/ (Accessed: 26 February 2022).

Wilhelm, T., Burghardt, M. and Wolff, C. (2019) ‘„To See or Not to See“ – an Interactive Tool for the Visualization and Analysis of Shakespeare Plays’, p. 10